Part 1 of a Series on How Refractive Index Shapes Optical System Design

In optics, some material properties are easy to spot. Others tend to stay in the background, quietly shaping performance without much discussion. Refractive index, often abbreviated as RI, falls into the second category.

It’s a single number you’ll see on a datasheet, but it has a surprisingly large influence on how light enters a material, how it moves through a system, and how an optical application behaves in practice. To understand why refractive index matters, it helps to have a basic understanding of what actually happens to light when it moves from one material into another.

A Simple Way to Think About Refractive Index

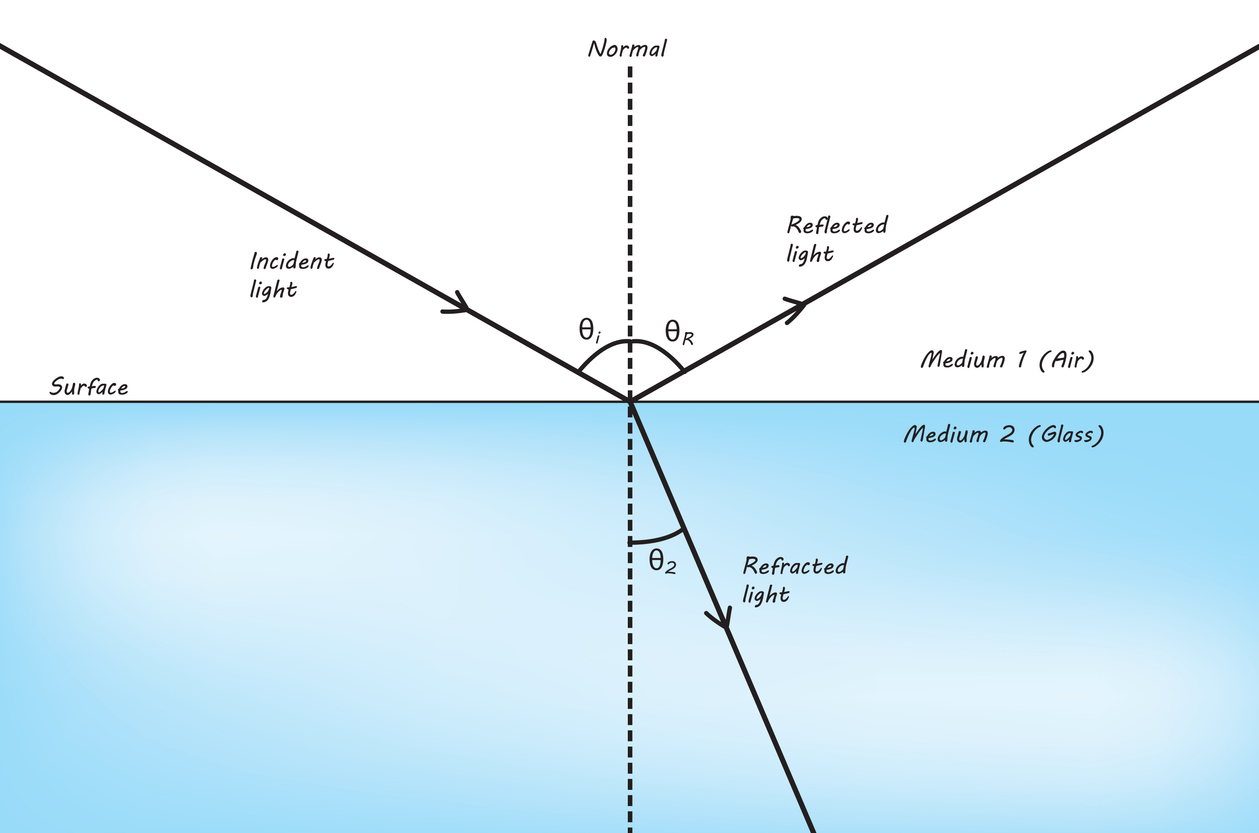

Light doesn’t behave the same way everywhere. Depending on the material it’s traveling through, light can slow down, bend, or partially reflect off a surface.

Most people have seen refractive index at work without realizing it. Put a pencil in a glass of water and look at it from the side. The pencil appears bent or broken at the surface. That happens because light changes direction as it moves from air into water.

Air and water interact with light differently. Refractive index is the way we quantify that difference.

Refractive index describes how much a materials changes the path of light passing through it.

- A higher refractive index means light is bent and redirected more strongly.

- A lower refractive index means light passes relatively undisturbed.

Refractive index doesn’t describe whether a material is clear or opaque. It describes how the material changes light’s path.

Everyday Examples Along the RI Spectrum

Air: With a refractive index very close to 1.00, air interacts only weakly with light compared to most materials. Light still bends, slows, and scatters slightly in air, but the effect is small enough that we usually don’t notice it.

Water: Water (RI ~1.33) interacts with light more strongly than air does. Water is clear, and light passes through it easily, but objects under the surface will appear shifted or distorted (as in Figure 1 above).

Glass: Glass (RI ~1.45) sits between water and common transparent plastics in terms of refractive index. It is very transparent, allowing light to pass through with little loss, yet it still bends and reflects light noticeably. That’s why glass surfaces produce glare and reflections, and why the edges and thickness of glass are easy to see. Glass shows that a material can be optically clear while still interacting strongly with light.

Common Transparent Plastics: Many everyday plastics used in lenses, light guides, and optical components have refractive index values in the range of roughly 1.49 to 1.60. These materials can be clear, but their higher refractive index makes reflections more pronounced and light bending more obvious.

Refractive Index as a Design Lever

Most solid materials used in optical systems fall within a relatively narrow range of refractive index. That constraint quietly shapes nearly every optical design decision, because refractive index influences not just how light bends, but how complex, sensitive, and forgiving a system ultimately becomes. In practice, refractive index often determines:

- how many optical layers are required,

- how tightly components can be packed,

- how sensitive performance is to surface roughness or defects,

- and how much margin exists before losses and reflections begin to dominate.

Higher-index materials bend and redirect light more strongly. This can enable compact lenses and aggressive geometries, but it also tends to increase surface reflections and amplify sensitivity to imperfections at material boundaries.

Lower-index materials interact more gently with light. They produce smaller reflections at interfaces and can appear more optically “invisible” within a system. These characteristics are especially valuable when the goal is to guide, isolate, or protect light rather than manipulate it aggressively.

The Rarity of Very Low Refractive Index Solids

Materials with a very low refractive index are uncommon – especially ones that are transparent, durable, and practical to use in real optical systems. When a solid material has a refractive index well below what’s typical for glass or conventional plastics, it gives optical designers more freedom in how light enters, moves through, and exits a system. Lower-index materials can simplify optical interfaces, reduce unwanted reflections, create cleaner transitions between layers, and enable designs that are difficult or even impossible with standard materials. This is where amorphous fluoropolymers (AFPs) become especially interesting.

Amorphous Fluoropolymers as Ultra-Low-Index Materials

Amorphous fluoropolymers are a class of fully fluorinated polymers whose non-crystalline molecular structure causes them to interact unusually weakly with light. In optical terms, this means they bend and slow light less than most plastics – a subtle distinction with significant design consequences.

Amorphous fluoropolymers exhibit refractive index values well below those of conventional optical polymers, typically discussed in the range of approximately 1.29 to 1.35, depending on formulation and wavelength. That places them much closer to water than to glass or common plastics, while still remaining solid, transparent materials.

This combination is rare. Most polymers cluster tightly around refractive index values near 1.5 and pushing significantly below that range usually requires accepting tradeoffs in transparency, durability, or processability. Amorphous fluoropolymers are unusual because they achieve very low refractive index without giving up optical clarity, chemical resistance, or long-term stability – qualities that matter in real optical systems.

Where This Leads

Understanding refractive index at this level helps explain why amorphous fluoropolymers show up in optical systems that push practical limits. Their unusually low refractive index gives designers greater control over how light is confined, reflected, and managed at material boundaries – especially in environments where losses, back-reflections, or thermal stress quickly become limiting factors.

In the next two articles in this series, we’ll look at how this single property is leveraged in two demanding applications:

- high-power laser optical fibers and,

- antireflective coatings for high-power optics.

Although the systems are very different, both rely on the same underlying advantage – using an exceptionally low-index solid material to solve problems that conventional optical polymers and glasses struggle to address.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is refractive index calculated from light speed or from angles?

Both. Refractive index represents how much light slows down in a material compared to empty space. In practice, it is often determined by measuring how much light bends when it enters the material. That bending is caused by the change in light’s speed, so angle-based measurements and speed-based definitions describe the same underlying property.

Is a lower refractive index always better?

No. “Better” depends on the application. High refractive index is useful when strong bending or compact optics are needed. Low refractive index is preferred when minimizing reflection or optical disturbance is more important.

Does refractive index affect transparency?

Not directly. A material can be very transparent and still have a high refractive index. Transparency describes how much light is absorbed or scattered. Refractive index describes how light is bent and redirected.

Why do many plastics have similar refractive index values?

Many common polymers share similar molecular structures, which leads to similar interaction with light. Achieving a much lower refractive index typically requires very specific chemistry.

Is refractive index the same at all wavelengths?

No. Refractive index usually varies slightly with wavelength. This is normal and is known as dispersion. For clarity, a representative value is often used.

Why is refractive index discussed early in optical design?

Because it affects so many downstream decisions. Once materials are chosen, many aspects of a design become fixed. Refractive index helps define those boundaries early.